For those familiar with My Brother’s Husband by Gengoroh Tagame, please read Tagame Gengoroh’s “Painting the essence of gay erotic art” (Esmralda, 2014) and Influential manga artist Gengoroh Tagame on upending traditional Japanese culture (Ishii, 2018).

Whilst I like to think of “My Younger Brother” as Japan’s first ever “gay manga for straight men,” even at the best of times the hurdles I needed to overcome as a gay artist creating a gay manga within a magazine that is mainly read by straight men were quite high. For example, to ensure that I didn’t cause any negative reactions amongst the [straight male] readers of the magazine, I had to pay particular attention to the plot. Therefore, if I employed the kinds of narratives that gay readers and those who enjoy BL would expect, perhaps the story wouldn’t move forward smoothly [for straight male readers].

— Gengoroh Tagame (Esmralda, 2014)

Terms and History

ゲイコミ geikomi

Geikomi (ゲイコミ) or “gay comic(s)” “refers to the genre of erotic comics published and marketed to adult gay men. Frequently called ‘gei manga’ (ゲイ漫画), it is different from the Boys’ Love genre in that its targeted audience is exclusively adult gay men. Therefore its contents are tailored to suit that audience” (Idling Chair, 2020b).

Specific common body type categories:

- ガッチリ gacchiri — muscular (robust, well built)

- ガチムチ gachimuchi — muscle/chub (slang: stocky, beefy)

- ガチデブ gachidebu — muscle/fatty

- デブ debu — fat

(Searching for these in tags (in Japanese) online can help you find geikomi content you’re looking for.)

薔薇 bara

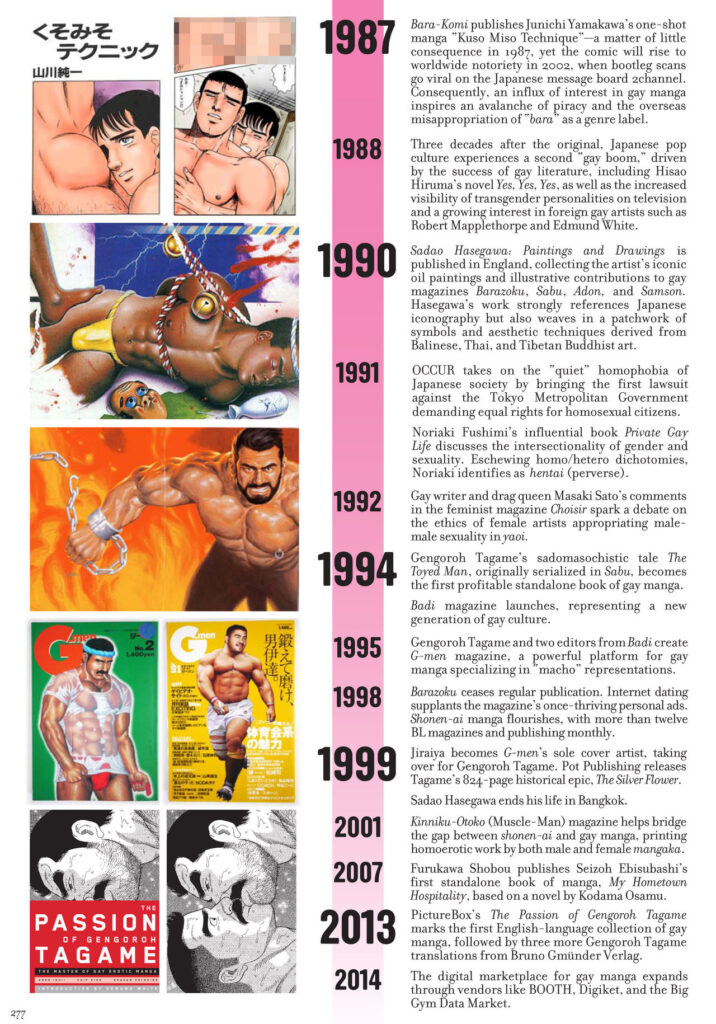

“Literally means ‘rose.’ Its common usage can be traced back to the first magazine catering exclusively for gay men in Japan, Barazoku (薔薇族) (Idling Chair, 2020c).”

[In] 1987 Bara-Komi publishes Junichi Yamakawa’s one-shot manga “Kuso Miso Technique”—a matter of little consequence in 1987, yet the comic will rise to worldwide notoriety in 2002, when bootleg scans go viral on … 2channel. Consequently, an influx of interest in gay manga inspires an avalanche of piracy and the overseas misappropriation of the term “bara” as a genre label. (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 277)

The title of Bara-Komi raises an important linguistic sticking point for Tagame: the widespread misuse of the term “bara.” Literally “rose,” bara is an antiquated slur for gay men. It took on a new layer of meaning in the 1960s as the title of the private circulation gay publication Bara, and the subsequent mass-market magazine Barazoku (Rose Tribe). “It was very shocking and sensational to publish something in the jargon of the hetero nomenclature for gays,” says Tagame. “It’s exactly like the word ‘pansy’ in English. Whereas gays probably don’t call each other ‘pansies,’ since it’s not necessarily a good thing, to reappropriate it was a big deal. But by the time I was getting bigger as an artist, that word was almost obsolete, and we no longer use it. It was important for us to call ourselves ‘gays’ and ‘homosexual’ rather than ‘bara,’ which is just what hetero people call us.

“Gay” became the primary identity label for homosexual men as a more internationalized concept of LGBT identity gained political and social ground in Japan. “By the 1990s,” Tagame remembers, bara “was totally obsolete, Barazoku magazine was becoming obsolete, and the whole nomenclature was about to completely expire. But in the early stages of the Internet, when people were on all these Internet boards, basically, the people running these forums were straight, so they called the gay board the ‘bara‘ board.

“Of course, the Internet is how foreigners discovered our work. They saw that this whole section was called ‘bara,’ so that’s how I believe foreigners started to use and appropriate that word. The word has come back to life, unfortunately, and I have to say personally, I’m sort of against it. I don’t call my own work ‘bara‘ and I don’t like it being called ‘bara‘ because it’s a very negative word that comes with bad connotations.” (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 40)

“Bara” at the very least is a largely outdated term and not modernly used as a visual/industry/umbrella term for gay men’s manga. It doesn’t necessarily universally refer to a buff visual or body style; it relates to a decades-old reclamation & popular magazine (Barazoku) that went out of style by the late 90s. While it’s fine for Japanese men to use it, outsiders calling all “buff” characters “roses” isn’t accurate—it’s outdated. In terms of industry and umbrella terms, it’s just “gay comics” = geikomi.

“Bara” becoming a staple of Western vocabulary was likely due to homophobic men on 2channel causing certain comics to go viral. Since the early 2000s, Anglophones haven’t bothered to update their language regarding it. Many gay Japanese men have compared the usage of “bara” to saying or calling a gay man a “pansy” in English. Since using “pansy” as an insult is less recent in English, a potential modern comparison could also be “fairy.”

People have reclaimed it; some people happily use it! Some identify with it, others don’t, but gay men’s media as an overall collective isn’t referred to, categorized, or sold as “fairy” media or “fairy” style, etc.

While internationally, the term bara has in one sense become synonymous with the type of fat guys Poohsuke adores, the artist typically associates the term “bara manga” with the more willowy men catered to and fawned over in what is now generally considered the phrase’s namesake magazine, Barazoku. Bara denotes a feminine male body type and manga language he had never strongly identified with, even as a younger artist contributing work to that very magazine.

“Bara is not a term that’s widely used in Japan, actually. Frankly, for the average gay Japanese person, the terms we use are more like gachimuchi (beefy) and debu (fat) or gei or homo manga but not bara, which means rose… But it’s not problematic really. Americans can use it, and if it means something to them, that’s great” (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 96)

— interview with Poohsuke Kumada, gei manga author (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 96)

“I personally think of the magazine Barazoku when I hear the word,” Mizuki says of the foreign term often used for gay manga, bara. “I even used to run pieces in it myself, but don’t think the association is apt. So I’d identify more as ‘gay’ than ‘bara.'”

— interview with Gai Mizuki, gei manga author (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 156)

Like the other artists in this book, Ichikawa sees “bara” as a contentious term. “It is always confusing to me when English speakers use the word ‘bara,’ not so much because it’s offensive, but because it’s so outdated. It’s a really old expression, like ‘pansy.’ It’s the same feeling when you hear that in English.”

— interview with Kazuhide Ichikawa, gei manga author (Ishii et al., 2014, p. 243)

The two reasons why I feel reluctant to have my work introduced as bara overseas are that first of all, there is no such genre as bara manga in Japan, and second, I don’t want gay to be reduced to a slang word such as bara.

… I feel like, “Feel free to misuse the word senpai in an American cultural context, but don’t bring it into my official work from Japan.” I feel the same about the word bara.

My personal impression is that you don’t really see the phrase “bara” much in Japan, even on the Internet. Even art on pixiv is clearly labeled as “for gays.” Rather, I feel like it’s foreigners who think such euphemisms are necessary.

Ba- bara…… Somehow, “bara” has completely taken hold as a label for Japanese gay manga (or even muscular BL manga) overseas, and it makes me feel really uncomfortable… (´・ω・`)

— Japanese user replying to Gengoroh Tagame on Twitter

People call it that in Korea, too. (;´Д`) The idea that “yuri” is used for women so “bara” is for men probably got its start on online anime forums in the 90s. That said, gachimuchi is popular now, and BL fans tend to correctly refer to it as gay manga, so bara has developed a somewhat dated nuance.

— Japanese user replying to Gengoroh Tagame on Twitter

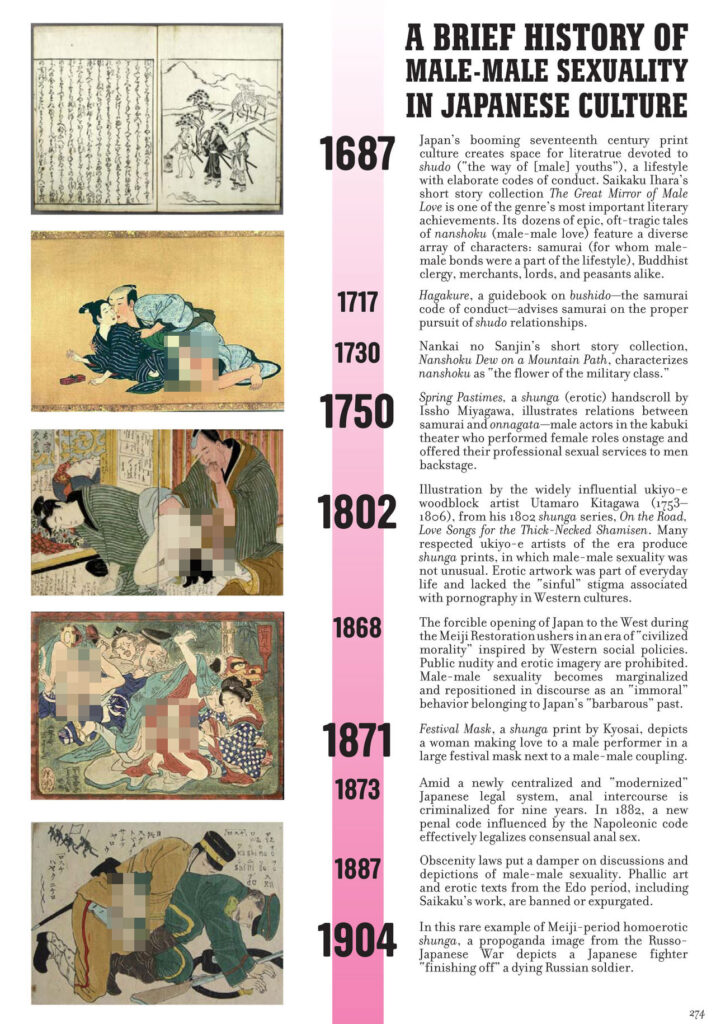

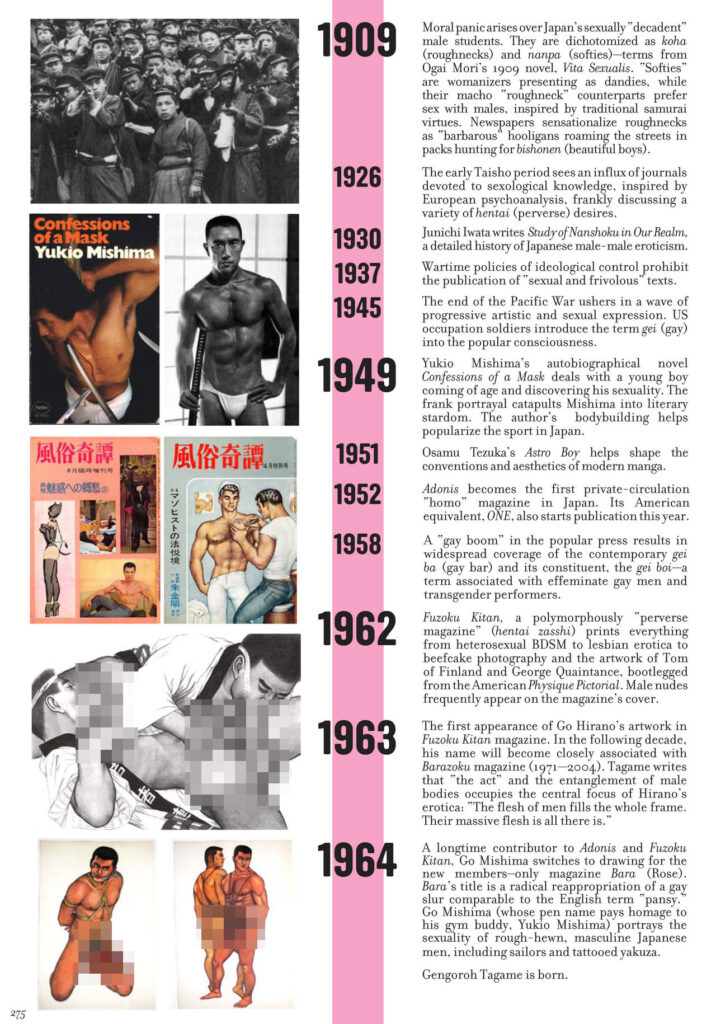

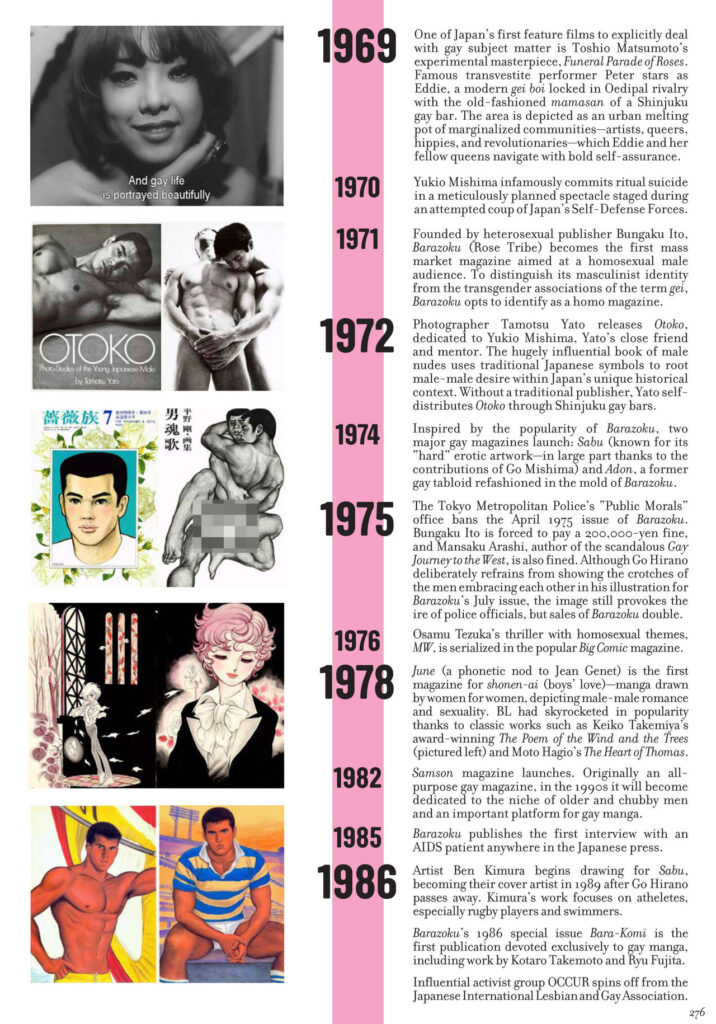

A brief history of male-male sexuality in Japanese culture

From Massive: Gay erotic manga and the men who make it (Ishii et al., 2014).

Geikomi and BL

Just because a gay man created something does not mean he necessarily made it with the intent of being “good” or realistic representation. It also doesn’t mean that he is representing all gay men equally.

People of any gender or sexuality may publish in both genres

When I look at gay art in comics as a critic, I get really anxious about that division precisely because the simplistic way of dividing it is that BL represents more romance, narratives, thinner body types, more effeminate characters. And then so-called ‘gay manga’ would be just more diesel, big guys and more hardcore sex, etc.

But what happens when the creator is a woman doing more hardcore work? Is that considered gay? Is it BL just because she’s female? Is it about the audience, or is it about the creators? So those are definitely things I think about a lot as a critic. Furthermore, going back to the gender of creators, that’s problematic as well because sometimes BL creators—and I’m speaking just from personal acquaintance with some of these creators—may be biologically female or identify on the page as heterosexual women, but sometimes they’re actually lesbian or transgender.

And then sometimes it’s the case that a woman will draw sort of muscle-y characters and then take on male pen names for publication in gay media. Which is also very… not problematic, but just raises questions, just how do we start to categorize? There are anecdotes from the editors of gay magazines who see these submissions, see a male pen name and assume that they’re men, write to (the artist), want to meet, when they meet, it’s a shock! (laughs).

— Gengoroh Tagame (Aoki, 2015)

Yarou Festival, a festival for gay comics, also doesn’t exclude women from participating:

“Is Yarou Festival for men? Is it for women?”

We do not operate with a specific male or female target audience in mind, nor is it specifically an event for people of any particular sexuality.

Historically, participants have tended to be about 90% men, but there are also many women who participate as exhibitors, and the number of men and women has become more evenly divided.

Many queer men view BL and geikomi as equally valid genres

These four men understood BL and geikomi as interconnected. They all variously argued that both BL and geikomi represent equally valid yet fantastic depictions of “gay identity” (gei aidentiti). For this reason, the four men saw no need to sharply disassociate BL from geikomi when discussing their consumption of gay media. Yoichi, whose consumption of both BL and geikomi is highly casual, explained that to conceptually separate the two genres made little sense; he stated, “They are both manga, two sides of the same coin… They have gay guys in them, even if they look different… so they’re gay manga.” This admission was despite the fact that Yoichi was a firm believer in the primacy of hardness and despite his denigration of soft masculinity. (Baudinette)

Geikomi is generally associated with being more sexually aggressive, while BL is associated with romance

Yaoi/BL, being produced by women for women, is more likely to reflect an understanding of gay intimacy premised on an ethics of care when compared to the models of gay intimacy emerging from within mainstream gay male culture. This suggests that yaoi/BL is the sort of subjugated knowledge that may have something valuable to contribute to the re-envisioning of gay intimacy, especially if coupled with the point … that yaoi/BL was born as a reaction to the formulaic constraints of marital heteronormativity. To paraphrase Halberstam (2005), yaoi/BL “culture constitutes … a counterpublic space where white [heteronormative and metronormative gay] masculinities can be contested, and where minority [gay] masculinities can be produced, validated, fleshed out, and celebrated. (Zanghellini, 2012, p. 128)

These conventions of the yaoi/BL genre are as removed from those of standard Western gay male pornography/sex as they could be. Indeed, I would argue that ‘activity/passivity,’ rather than ‘dominance/submission,’ provides the most accurate conceptual framework for understanding much (if not all) yaoi/BL work. This does not necessarily contradict the observation that producers and consumers of the genre ultimately assert “the right to imagine sex which is not politically correct: that is sex which derives its interest from imagining power differentials, not equality” (McLelland, 2005, p. 74). The reason is clear: power asymmetries do not necessarily have to lead to relationships of dominance and submission. (Zanghellini, 2012)